- Home

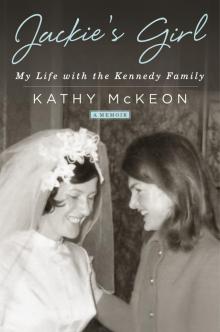

- Kathy McKeon

Jackie's Girl Page 5

Jackie's Girl Read online

Page 5

When the rest of us came home from school, Mary was lying very still in Mam’s bed. I couldn’t see the rest of her beneath the sheet, but I saw her ghostly face, covered with the white salve Mam had made with baking soda and water. Mam’s blistered hands were white with it, too. Mary’s hair was all burnt off.

The ambulance came and took my little sister to the hospital in Monaghan, but they couldn’t do anything for her there, so they transported her to the bigger hospital in Dublin, where she died a day or two later. There was no money for a hearse to bring her home, so Dad placed her casket in the back of a neighbor’s borrowed station wagon for the three-hour trip. There was a funeral Mass that I no longer remember, and Mary was buried in our family’s cemetery plot, with a simple cross marking her grave. I don’t remember Mam, or any of us, ever talking about her. It was just something we all understood must be kept inside.

December rushed past in a flurry of farewells as Briege and I got ready to leave on January 8, 1964, barely a month after my nineteenth birthday. The night before we left, the camogie team threw us a party and presented us each a trophy on a marble base. I packed it into my ancient secondhand suitcase, along with my prayer book and a glow-in-the-dark Christmas ornament Aunt Rose and Uncle Pat had sent one year, a holly wreath with a nativity scene in the center. We never did have a Christmas tree, but it had served as a night-light when I was growing up, and I was quite attached to it still.

On the way to the Dublin airport, I checked my passport and ticket again just to make sure this was real. (Only when I got the passport had I learned my given name was actually Catherine, not Kathleen—I was a changed person before I even boarded the plane.) My Irish Airlines ticket was stamped “ONE WAY” in bold letters, a reminder every time I looked at it that there would be no turning back. From an observation deck inside the airport, we could see other planes taking off, plumes of what looked like smoke trailing behind them. I nudged my sister in alarm. “Oh my God, Briege, we’re in trouble, look how fast they’re going!”

Our plane sported a green shamrock on the side, and I wasn’t sure whether to be reassured or concerned that the national symbol for good luck served as the airline’s logo. We boarded and I fastened my seat belt tight. The stewardess began giving instructions, telling us we’d find our life jackets under the seat. I dove down and began groping for it, thinking we were supposed to put them on and wear them until we landed again. “No, no, you eejit,” Briege admonished me. “Not now. Only when we’re crashing.”

Then the plane was hurtling down the runway, everything rushing by sideways out the tiny window. The wheels lifted up with a loud whining noise and heavy jolt, and there I was, flying. Fear gave way to excitement. Higher and higher through the clouds we climbed, Ireland becoming just a green speck below, growing ever smaller until, too fast, it slipped away.

THREE

Inside the Bubble

The frozen half-smile the outside world saw in formal portraits and scores of magazine photographs of Jacqueline Kennedy never hinted at the girlish sense of humor I sometimes glimpsed in the privacy of her own world. Like my squeaky shoes, the unique circumstances of her life conspired to create some great slapstick comedy at times. Seeing Madam’s delight in those ridiculous moments made me feel a kinship I had never expected to, as if I had slipped inside a bubble that had a secret bubble within that no one on the outside could see. More and more, it was starting to feel not so much that I had taken Provi’s place there but that I was finding my own. It was during those silly, spontaneous moments with the family that I felt most myself.

Once on a winter break in Palm Beach, Madam and her sister, Lee, were basking by the pool one afternoon while John, Caroline, and their cousins Anthony and Tina played in the water. The boys would have been maybe five or six then, and the girls a few years older. The Radziwill governess, Bridget, and I were getting ready for a rare night off in town. When I first got to New York, I had spotted an ad in the paper for cosmetology school. I had always loved styling my friends’ hair back home and experimenting with the latest fads, like using beer as setting lotion. Seeing that ad got me excited by the thought that I could maybe learn the trade by taking classes in the evenings and on my day off, and I immediately enrolled. I only made it to a couple of sessions before my overprotective Aunt Rose found out and put a stop to it, saying it was far too dangerous for a young woman to be riding the subways alone at night. I still enjoyed playing beauty parlor with willing friends and coworkers, though, and I had spent a few hours that afternoon in Florida setting, teasing, and styling Bridget’s hair into a half-up, half-down beehive with a cute little flip at the ends.

We came out to the pool to show off the final result. Madam looked up from the paper she was reading to rave over the hairdo. Bridget spotted Anthony running along the side of the pool and went to intercept him and make him slow down, but she was standing too close to the edge and he was moving too fast, and she ended up getting accidentally pushed in.

“She can’t swim!” Anthony yelled, even as a Secret Service agent appeared like Superman out of thin blue air and dove in—dark suit, shoes, tie, sunglasses, gun, and all—to pull out the flailing governess.

The elaborate hairdo I had constructed was now plastered down over Bridget’s face. It looked like she was being smothered by a mad otter. Bridget was unharmed but wailing and sputtering Gaelic curses. On her chaise longue, Madam was hiding her face behind her newspaper, but I could see the paper shaking like mad and could tell she was struggling mightily not to laugh out loud. Such a perfect lady, she could even carry off a soundless guffaw.

Like New York City, she was a riddle to me, both less than I expected and far more than I imagined.

It was funny how the paparazzi could so easily capture her aura of mystery, yet her more beguiling ordinariness always eluded them. She took my breath away every time I saw her in one of her couture gowns and jewels, off to the Metropolitan Opera’s annual gala or some other star-studded event. “You look beautiful, Madam,” I always told her, meaning it every time. And every time her face would light up and she would smile, thanking me and giving me a little hug on her way out. But a different, even lovelier light came through when she was at home, in her favorite tee shirt or turtleneck, in those tender hours when she could just be a devoted mother or friend, unscrutinized by the world. I was touched whenever I saw her eating lunch in the kitchen with John while Caroline was at school, sweetly indulging his endless questions and listening with delight to his funny little stories. Every day, I knew I could find her at her desk, deep in thought as she wrote long letters or dashed off quick notes to people who—like her brother-in-law Bobby, or her dear friend Bunny Mellon—might well be living mere blocks away. She went through rolls and rolls of stamps, stashed in a white wicker basket at her feet. She hadn’t been widowed even a year when I came to her, and though I hadn’t known her before, it felt good to see these glimpses of contentment. To know that she was going to be all right.

She was a handsome woman, to be sure, but to tell the truth, if you didn’t know who it was you were seeing, your jaw mightn’t drop the way it would if, say, Elizabeth Taylor or Grace Kelly happened to glide past on the street.

What drew you in with Jacqueline Kennedy wasn’t perfection; it was a presence. It wasn’t how she looked, but how she was composed.

Small wonder that most of us who worked for her tried to imitate her, in our own clumsy ways. Provi initiated me into that club while we were relaxing in the little staff lounge after a long day’s work during my very first week. We had begun to strike up the beginnings of what would prove to be a lifelong friendship of sorts, often prickly but as stubborn, in the end, as both of us. Madam’s recent move from D.C. to N.Y. had turned Provi’s own family life upside down as a single mother with two sons. The youngest, Gustavo, was just a few years older than Caroline, and had been left in the care of Provi’s aging mother back in Washington while attending the private school whose tuition, Provi confide

d, the Kennedys had always paid. Madam also paid for Gustavo to fly to New York each weekend to see his mother, Provi added, but such generosity couldn’t make up for what Gustavo was missing. It had been agreed that Provi would stay on for a couple of months to whip me into shape and make the transition as smooth as possible for Madam before returning to D.C. to rejoin her family and work in the offices of Robert F. Kennedy. “I need to get back home and take care of my son,” she said, taking a deep drag from the cigarette she held in a slim plastic holder similar to the ones I’d seen Madam use when she lit up the occasional L&M in her private quarters. Provi tilted her small head back and to the side, pursing her lips to blow out a plume of smoke with a well-rehearsed air of boredom.

“Take one,” she said, offering her pack.

“No, thanks, I don’t smoke,” I said.

“You should try it,” she urged, tapping one out for me. I shrugged and put the cigarette to my lips and lit it, inhaling ’til my lungs started to sting. I exhaled slowly, enjoying the cool relief. This was fun! I felt terribly grown-up, and before that first cigarette burned down to ash, I had become an enthusiastic smoker. It wasn’t a cheap habit, I soon learned, and my brand of choice was OPCs—Other People’s Cigarettes. I also salvaged the stale or crumply ones I found in Madam’s pocketbook or evening bag when she switched purses. Provi had told me Madam had to have a few fresh cigarettes tucked inside whenever she went out, along with her favorite lipstick, a small brush, and a couple of quarters in case she needed to make a phone call. (She never carried money. She would borrow a few dollars off the doorman if she needed to tip a cabdriver, then send one of us right back down to repay him.) Madam didn’t smoke in public and rarely used the ones in her purse. I was certain she wouldn’t want the ones I was saving, but I was too ashamed to just come right out and ask her, even though she occasionally borrowed a smoke off me in a pinch.

Smokes weren’t all I intercepted. Toiletries, oh, were those ever the grand prize: I could hardly wait for Madam to run low of the special bath oil she got from France; it smelled heavenly, and there were always a few drops I could coax out of a discarded bottle if I added a little hot water before shaking it into my own tub. Even better than the dregs of Madam’s bath oil were the final drops of her perfume. Her favorite was Joy, a French fragrance said to be the most expensive in the world because it took more than ten thousand jasmine flowers and over three hundred May roses to create a single ounce. It was up to me to monitor every product Madam used to ensure she never ran out of anything, whether it was a wand of mascara, a bottle of shampoo from her hairdresser, Mr. Kenneth, or a roll of breath mints. As soon as she got close to using up the bottle of Joy she always kept on her mother-of-pearl vanity table, I would order a replacement through Nancy Tuckerman, then recycle the empty for myself when the new one arrived. The heady scent lingered even when the vial was bone-dry empty, and I could scent my lingerie drawer with it.

Madam loved to surprise people with little gifts for no reason; she was always buying books to send off to friends she thought might enjoy them. Whenever I dropped by in later years to say hello with my small children in tow, she would always go searching through closets or drawers for some toy or trinket to give them. I had benefited from that same generous impulse many a time while I was living at 1040 and Madam decided to cull her collection of peignoirs or costume jewelry or scarves. “Kath, is this something you would wear?” she might ask, offering a choker of rhinestone flower buds or a silk designer scarf in tasteful maroon and beige plaid. Nancy Tuckerman even let me pass along some of John’s and Caroline’s castoffs to some struggling Irish relatives with a houseful of children. “Just make sure to remove any name tags sewn in them,” she reminded me. (Caroline probably would have paid me to get rid of the smocked pastel cotton dresses from England that her mother insisted she wear; she absolutely hated them.)

Though my duties didn’t include minding the children every day, I quickly fell into entertaining and keeping an eye on them as I went about my business, particularly John, who wasn’t in school yet. John was hyperactive and had been prescribed medication for it; we also had to keep him away from sugar as much as possible or he’d really start bouncing off the walls. It wasn’t that he was destructive or bratty, but both his energy and curiosity were endless. He would get up before the rest of the household, then proceed to make a racket rolling his favorite wooden truck up and down the hallway until someone—me, generally—came out to shush him.

“Let’s go make pancakes, Kat-Kat!” he would suggest, pulling me by the hand to the kitchen.

“John, we’ll get in trouble,” I protested. The cook hated to come in and find our mess.

“We’ll tiptoe,” John whispered. It was hard to say no to John or tell him he had to wait for Maud to get up to start his own busy day. If I didn’t come out of my room to keep John company, he would barge in at 6:00 a.m., pretending he was looking for his dog. Shannon had discovered that I appreciated leftovers and was always willing to share the haul from my midnight raids, so he had wisely taken to sleeping under my bed. Officially he was considered John’s dog, but Shannon belonged to whoever fed and walked him, and once I started doing that, there was no going back. He was a terrible beggar, and I could never refuse his plaintive gaze. He followed me everywhere.

“Kath, did you bring Shannon in here?” Madam would groan sleepily when I came to wake her some mornings. “I know you did, I can smell him!”

I usually grabbed the dog’s leash and took him with me when I walked to the newsstand to get Madam’s papers and magazines. (Tabloids were her guiltiest pleasure.) When John begged to go one morning, I went to ask his mother if it was okay. She was grateful for the favor but didn’t think to tell Maud, who was still asleep and went searching high and low for John once she got up. Someone finally mentioned that I’d taken him out. Maud had worked herself into a fine lather by the time we sailed back through the door. The children were her charges, she upbraided me, and I was not to take them anywhere without her permission.

Maud’s high-and-mighty tone got under my skin, and I was sorely tempted to point out that the only reason I was minding John in the first place was because she had been sleeping. But she was old enough to be my grandmother, I reminded myself, and this wasn’t a battle worth fighting, since I had nothing at stake.

“Madam said I could,” I simply told her.

“I am the one you need to ask,” Maud huffed. Like Provi, she had worked in the White House, where the family’s personal staff had the added support of all the White House servants. I was Madam’s personal assistant, though, not Maud’s. When I initially arrived at 1040, Maud tried to tell me I had to make the children’s beds and clean out Caroline’s birdcage. I knew better, and also knew if I let myself be cowed by her from the get-go that it would only get worse and more of her chores would end up migrating onto my daily task list.

“No, I don’t. I didn’t come here to do that. That’s not my job at all,” I told her bluntly. “That’s your job.” She hadn’t bargained on me showing any gumption. She scowled and turned her heel.

It was no secret among the help that Maud was nearing retirement, and Madam was just waiting for the right time, and the right replacement, to ease her out. Caring for John and Caroline as babies wasn’t as physically exhausting as caring now for active kids of four and seven. Caroline could quietly amuse herself for hours at a time, but John was a boy in perpetual motion, and Maud was over sixty.

One afternoon soon after I started, I heard Caroline and John in their back hallway fighting about something. John loved to torment his sister by sneaking into her bedroom to let her parakeets out of their cage, or scatter her toys. She seemed to have gotten the better of him this time, though: I heard a door slam and Caroline’s triumphant shout.

“You’re not coming out now!” Next came the sound of someone banging on a door, and a rattling noise I couldn’t place. The commotion carried on with no indication that the usually strict govern

ess was stepping in, and I realized that Maud was likely napping through it all. I went to the children’s wing to investigate. Caroline had retreated, and the red-carpeted hallway was empty. The racket was coming from John’s bedroom, where I was horrified to see a sliding-chain lock fixed to the outside of the door. John was trapped on the inside, rattling to get out like a gorilla in a cage.

“Let me out! Let me out!” he cried. The chain only allowed the door to open a few inches. I could see John’s little face peering through the gap.

“Kath? Can you let me out?” he pleaded.

I had seen the handyman working on the door a few days before but hadn’t noticed that it was an outside lock he was installing. Maud had been supervising. Now that she was in her own room snoring away, I put two and two together: John no longer needed a nap, but Maud did. Problem was, John would never stay put when Maud tried to put him down to sleep for a couple of hours so she could do the same. He’d bounce right up and go pester the cook in the kitchen, or come ask me to play, or even slip off into some other room to explore and look for mischief without anyone knowing he was on the loose. That generally ended badly, though not always as dramatically as the time he found an old firecracker in a buffet drawer in the dining room and the explosion brought the Secret Service barreling into the apartment with guns drawn. The blast had shattered a big decorative platter and filled the room with smoke. John was nowhere to be seen, of course. Madam hurried to his room, where he was scared and crying, but thankfully unhurt. Maud obviously thought that locking John in his room was the only way to keep him contained while she took her customary snooze in her room just across the hall, but I couldn’t believe she had done such a dangerous thing. I immediately slid the lock open, and John catapulted out. I hurried off to find his mother.

Jackie's Girl

Jackie's Girl